A Brief History of Women Entrepreneurs

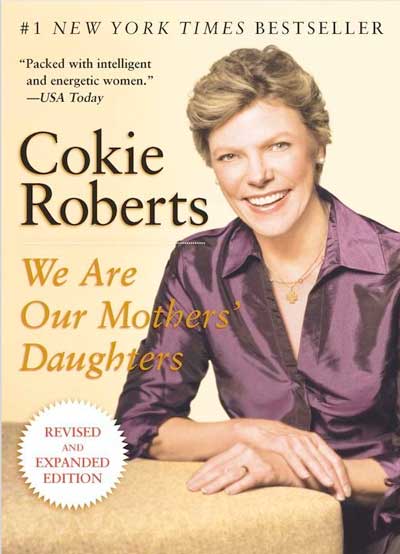

I recently finished reading We Are Our Mothers’ Daughters, by Cokie Roberts. The book is about the changing roles of women in American society. Roberts examines women’s participation in a variety of fields, including athletics, medicine, business, and the military. Each chapter offers a brief look into the lives of women who have redefined a woman’s place, and the book is very accessible for the average reader.

I recently finished reading We Are Our Mothers’ Daughters, by Cokie Roberts. The book is about the changing roles of women in American society. Roberts examines women’s participation in a variety of fields, including athletics, medicine, business, and the military. Each chapter offers a brief look into the lives of women who have redefined a woman’s place, and the book is very accessible for the average reader.

Two of the chapters that I found the most interesting were about women as entrepreneurs and women as philanthropists. In the “Entrepreneur” chapter, Roberts tells the stories of three women who made a fortune by capitalizing on traditional women’s roles. For example, Bette Nesmith Graham invented liquid paper when she was a secretary who had grown tired of retyping a whole sheet of paper if there was a single mistake on the page. Graham concocted the recipe for liquid paper in her kitchen blender and eventually went on to make millions with her invention.

Madam C. J. Walker was woman who made a fortune simply by inventing something that would improve her daily life. Walker noticed that many African American women had lost their hair because of the harsh chemicals and the hot combs they used to straighten their locks. Walker invented a hair cream to help improve the health of women’s hair. She started selling the product door-to-door and wound up hiring thousands of women to sell her hair product.

Margaret Rudkin launched the successful firm Pepperidge Farms almost by accident. Her family doctor told her that her son’s asthma was related to an allergy to the bread he was eating, so Rudkin developed a new, wholesome bread recipe. When her son’s health improved, Rudkin started selling the bread to doctors and other people who were interested in healthy eating. The business eventually expanded so that Rudkin and her staff were soon baking nearly 4000 loaves of bread an hour, all of them kneaded by hand.

One thing that stands out about all three of these women is that they were determined to provide employment opportunities for women. Rudkin only hired women to bake her bread because she claimed that their hands were better suited to the task than men’s. Graham was one of the first CEO’s to offer childcare facilities for her employees. And Walker made sure that only another woman could succeed her as CEO when she retired.

Roberts’s book also documents the role of women as philanthropists. She cites an interesting statistic that says that by 2010, women will control 60% of the wealth in this country. I find that statistic hard to believe, because women still earn only 78 cents for every $1 that a man makes. However, since the chapter on philanthropy mainly applies to women who are in the top 1% of the socio-economic ladder, I guess the statistic isn’t that hard to believe. Roberts notes that women give their money differently than men do. As Nina has previously discussed here on Queercents, women often pool their resources by joining giving circles so that their donations can have a larger impact. Roberts argues that women’s philanthropy is inherently tied to their traditional role of caregiver, but I don’t really care for that analysis. I think it’s fair to say that women are more likely to give to causes that improve the lives of women and children, but I don’t like the idea that women are inherently nurturing and that this is the only thing that motivates them to get involved with philanthropy.

Nevertheless, I really enjoyed We Are Our Mothers’ Daughters and I highly recommend it, especially for a book group discussion.

David Bowie as Cokie Roberts?

Leo, I hadn’t ever noticed the resemblance before, but I think you might have a point. ;^)

Took me so long to get this one I didn’t want

to chance missing the deal again. 4464, and we will provide you with further

instructions on where returns should be shipped and the amount you

will be refunded. Most of the time the problem is the

rice and water proportion; we must make sure

that we put 2 cups of water for every cup of uncooked rice.